Dance as Non-Verbal Communication in Applied Dance

Introduction:

In this article I will be looking at Dr. Judith Hanna’s theory of dance as non-verbal communication, and apply it to teaching methods of dance. I am a Middle Eastern Dance Instructor of 16 years, and my background is in Western ballet, and Modern Dance, particularly, Martha Graham style. I first approached this paper as a study of Dr. Hanna’s theoretical works, but once I contacted her, and got into her work, I saw that she is very much into bringing her theory of dance as non-verbal communication into the school classroom.

As a dancer, I found this very exciting, as all of the fields of dance have different methods of teaching, but none of these fields are communicating or sharing their methods with others. These fields are classical ballet; modern dance; tap; bellydance; African dance; jazz; fitness (particularly, Zumba, the latest craze). All of these dances are taught at universities, but in very different settings. There are many reasons for this, degreed programs have their priorities for academics, and fitness non-degreed programs have their priorities with getting high numbers of participants to qualify for their funding. Somewhere in the red tape students are getting caught between administrators’ needs, and the best teaching methods are not always used. There is also an elitist culture in the dance world, where each genre sticks to their group, and judge dances of the “other” as being “not real dance”, ballet being the worst offenders. There is not much sharing of teaching methods between dance genres because of this lack of communication, although the last ten years or so have shown improvment.

I have a theory about ballet and how it is taught, and other dance forms have based their teaching on ballet. Ballet is a feudal system; it began during feudal times, and is based on the royal court culture. The King is the artistic director, and he owns the artistic license to the “land”, or the company. The serfs are the corp dancers who make up the majority of the company. They have little or no artistic input into the dance, and they must obey the “king” and his artistic whimsy. The majority of the fruit of their labor is cultivated only to give back to the “king” for his rewards (grants, funding gifts, etc.), while the serfs themselves get paid very little, and are not respected for their labor; only the soloists are recognized.

Fitness, and I am using Zumba as the most liberal example, is the extreme polar opposite of this model. Zumba, which is new Latin dance fitness created by Columbian native, Beto Perez, is becoming increasingly popular, because individuals are liberated from the strict technique controls of the dance classroom. Students are allowed the space to play and be creative; they are given a basic pattern on which they can improvise upon. Dancers feel like they are dancing right from the start; they feel like they are “saying something” with their movement that is unique to their sense of identity. There is a sense of empowerment to Zumba that is the polar opposite of ballet.

In between these two extreme models is Middle Eastern Dance. The most “serious” dancers in this genre follow the ballet model, however, this relies upon technique and choreography. Middle Eastern dance, and “bellydance” in particular, is the solo improvised dance of the “Arab World”. Being that it is improvisation based, there has been no codified style of how to teach this improvisational style of dance. The issues of gender and power largely weigh into the methods of teaching dance, also. It has been a primarily male dominated sphere, where men rule, and women do the work, despite it being a women’s dance.

My plan for this paper is threefold:

- Discuss Dr. Hanna’s theories in broad terms.

- Take a look at a few of her books and articles specifically.

- Look at the applied dance possibilities, and how I have interpreted her Communication Theory for teaching Middle Eastern Dance.

- Judith Hanna: who is she?

Dr. Judith Hanna is a dance anthropologist who is a Senior Research Scholar in the Department of Dance and an Affiliate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Maryland, an educator, writer and dance critic. She received her Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1976 and has written numerous books and articles since then. It is important to know, however, that Dr. Hanna started as a dancer and a dance teacher, but she stopped teaching dance when she became a dance anthropologist. As a dancer I believe this adds to her credibility, as dance must be embodied to be cognitively understood; dance must be learned through the body. To speak of dance and not dance is not complete research.

She covers many areas of dance:

- On her Website: judithhanna.com

- American Dance

- Criticism

- Dance in African & the Diaspora

- Education & Dance

- Exotic Dance

- Gender & Dance

- Health & Dance

- Identity & Dance

- Religion & Dance

- Theory, Methodology & Dance Writing

When I first picked this topic, I immediately contacted Dr. Hanna through email to ask her about her work, as we are both on the same dance email list-serve for academics. She was not only helpful, but was a joy to communicate with, and I learned a lot from our exchanges. I asked her, “How do you use theory in your research?” She answered,

“I am interested in the relationship between text (structure, action, style) and context – I seek meaning in movement – from narrative to play with form.”

The theories she employs are: “Communication Theory”, for dance it is multi-channel communication, particularly the Kinesthetic channel; “Cognition Theory”, for dance it is Interpretation/Meaning. Dance as text; how does context change it? Also, how does Hanna use Dramaturgy theory to describe context? These were some of the questions I had in my mind before I approached her works.

When I asked Dr. Hanna about Communication Theory, and that I was going to first read her book, To Dance Is Human, she replied that perhaps I should read her article, “A Nonverbal Language for Imagining and Learning Dance Education in K–12 Curriculum”, as it explained her theory in a more succinct way, and also showed how it could be applied. As a dance teacher, and someone who is researching cognition and the role of imaginative play in learning, and as a homeschooling mother, I found this to be the best launching point into her theory. However, I do feel that it is important to look at what Dr. Hanna defines as communication theory for dance, and to take a look at her semiotic model of non-verbal communication for dance. This model is found in her book, To Dance is Human: A Theory of Non-Verbal Communication (1979).

Communication Theory in Dance-

Communication Theory is mainly concerned in broad terms with how humans communicate, and the meanings they ascribe to that communication. It is as basic as a sender transmitting information to a receiver, and political scientist and lead communication theorist Harold Lasswell summed it up in this working definition:

“Who says what to whom in which channel with what effect.”

Symbolic Interactionists and Phenomenologists have latched onto communication theory, as it has to do with the individual and the development of identity to make meaning out of interactions with the larger structures of society. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communication_theory, 4-21-11)

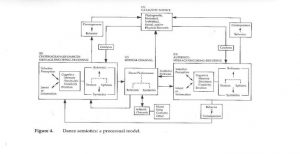

The invocation of the feedback loop by Doede Nauta in his book The Meaning of Information (Stone, p130) is in the semiotic-cybernetic model of communication, and is what Dr. Hanna uses in her semiotic model. This basically asserts that each dance performance is influenced by a myriad of feedback loops, which in turn alter the performance, and also subsequent performances in the future. This multi-channel communication model is essential to understanding that the kinesthetic channel is but one channel operating during a dance performance; also, dance is just one type of non-verbal communication.

Below is Dr. Hanna’s working model of dance as non-verbal communication:

Dance Semiotics: a Processual Model (Hanna, p 79)

As we can see from the diagram there are four main actors in this model

A) The Catalytic Source: phylogenetic (natural world), historical, individual, social, and/or physical elements. This has catalysts that create behavior with consequences to:

- B) The Choreographer-Dancer: Message Encoding-Decoding: selective perception, intent or information influenced by cognitive memory structures, emotion and creativity; also referents, or referring to past performances, a sort of reflexivity within the genre; this goes onto influence the:

- C) Medium-Channel: this is the dance performance itself; it is influenced by all channels, particularly the audience and adjunct channels such as music, song choice, costume, and other factors. This leads us onto the last channel of feedback:

- D) Audience: Message Encoding-Decoding: also uses selective perception, intent or information influenced by cognitive memory structures, emotion and creativity; also referents, or referring to past performances, a sort of reflexivity within the genre; it is interesting to note that this is the only stage in the communication that has feedback going back to the choreographer-dancer; the behavior of the audience and their reaction to the dance performance has consequences that have a feedback loop to the choreographer-dancer.

“A Nonverbal Language for Imagining and Learning: Dance Education in K–12 Curriculum” (2008)

Now I will use this article by Dr. Hanna to explain dance as non-verbal communication more in depth, and how it can be used in the classroom in applied dance. She uses theory that is pertinent to dance education from different fields, and she is looking at how emotion, language, non-verbal communication, dance, assessment (grading) influences cognition and learning in the classroom. The format of her article is as follows (Hanna, p491):

- The history of dance in academia: and subsequently K-12 education; key concepts of dance, and its ability to pack and unpack meaning.

- Academic history:

- 1900-Modern Dance split from Ballet, and began a philosophical debate on the nature of dance.

- 1925-Margaret Newall H’Doubler established the first dance major in the physical education department of the University of Wisconsin; her approach was biological and kinesthetic, which made dance recognized as a science. She taught her students the intellectual, physical, and emotion dimensions of dance (p492).

- 1970-80’s-Dance scholarship blossomed, and split off from physical education to homes in fine arts and education departments; first time offering doctorates in dance.

- 1990’s-Government funded artists in the schools programs and merging of the disciplines of medicine, computer and information science have been areas that dance has collaborated.

- Key Concepts in Dance:

- Hanna’s Definition of Dance:

“Dance can be conceptualized as human behavior composed of purposeful, intentionally rhythmical, and culturally influenced sequences of nonverbal body movements and stillness in time and space and with effort” (p492)

- Purpose

- Emotion

- Culture

- Symolization

Packing and Unpacking Meaning: How Dance Encodes Meaning-

- Six Symbolic Devices to Encode Meaning:

- Concretization

- Icon

- Stylization

- Metonym

- Metaphor

- Actualization

- Eight Spheres of Communication in which the Devices Operate:

- Dance Event

- Total Human Body in Action

- Whole Pattern of Performance

- Sequence of Unfolding Movement

- Specific Movements

- Intermesh of Movements with other Communication Modes

- Dance as a Vehicle for Another Medium

- Presence (Emotional Impact)

- The evidence of the power of non-verbal communication: comparison of verbal language and body language of dance;

- Movement as an Evolutionary Tool: Survival of the fittest.

- Verbal Language and the Body of Language of Dance Compared– Both Contain Ambiguity and Engender Cultural Transmission by:

- Arbitrariness

- Productivity

- Duality of patterning

- Verbal language exists only in the temporal, whereas dance involves the temporal plus three dimensions in space.

- The Brain in Verbal Language and Dance:

The thinking processes of verbal language expression, comprehension, abstract symbolic and analytic functions, sequential information processing, and complex patterns are controlled by the Broca and Wernicke areas in the left brain (p494). However, this only covers half of the knowledge needed, and motor sequencing and intention are covered by the left brain, too. The left brain controls the process of dance making, conceptualization, creativity, and memory; this is similar to how poetry is learned in the brain, but with different procedural knowledge. In the right brain are the controls for nonverbal processing of spatial information, music, and emotional reactivity (p 494). Dance forces our brain to use both sides at the same time, and especially the corpus callosum, which is the blanket of nerves that cover the two sides and is the highway for communication between the two. The left side of our brain spells out the words and the right side creates patterns for these words.

- Multilingualism and Multiple Dance Genres: Learning to dance creates the same neural pathways in the brain that learning multiple languages does.

- Language and Thinking: Dance conveys complex thoughts simply and efficiently.

- Evidence of the Power of Nonverbal Communication From the Hand Alone: Hand gestures become image and analog besides speech. (p. 495)

- Dance Uses the Hand and the Entire Body to Communicate

Multi-channel gestural system of non-verbal communication.

- The mentality and matter of dance: is the prominence of how cognition, emotion, and kinesthetic intelligence merge together in the student, and how dance education can help bring these elements together.

- Multiple Ways of Learning Through Dance: According to Gardner learning in dance happens in a symbolic system of intelligences, bodily or kinesthetic intelligence is a just one form of thinking, an ability to solve problems through “control of one’s bodily motions” (p 495). Other forms of intelligence are: linguistic, musical, logical-mathematical, spatial, intrapersonal, inter-personal, and naturalistic.

- Dance Impact on the Brain: Dance rearranges neural pathways in the brain. It has the most impact on stopping Alzheimer’s disease; it cut risk by 76%.

- Thinking Through Moving Images: Dance as moving images. The eye has understanding, and using observational skills, dance can improve students in cognition.

- Declarative and Procedural Knowledge: technique rules vs. application of the rules (performance and improvisational ability).

- Emotion: Feelings about learning dance, and performing.

- Critical Thinking: The main focus of dance in academe is the process of dance-making, learning that the solution to a problem can take many forms (p 497).

- The practices in K–12 education as a performing and a liberal art, and dance as applied art: she shows illustrative research that proves that dance education reverberates to other areas of the student’s learning;

- A Performing Art: Pre-professional programs; classical ballet does not teach the dancer how to choreograph.

- A Liberal Art: Interdisciplinary; dance for every-body.

- An Applied Art:

- Dance integrated with other subjects:

- Assessing nondance knowledge:

- Teaching for transfer of learning:

- The Impact of Dance Education Practices:

- Acquisition of learning skills

- Learning out of perceived necessity

- Enhanced Learning

- Continuum of Offerings

- Common Types of Partnerships

- Teachers who use the arts in their teaching practice

- The future of dance education:

Now that we have looked at the theory of dance as non-verbal communication we will take a look at how it is applied in three different settings, the first a class that Dr. Hanna taught and the format she used, the second an adult bellydance workshop that I taught at the Indiana Dance Festival, and the third in a children’s Modern Dance performance. This is the perfect launching point to show how I have interpreted Dr. Hanna’s theory of dance as nonverbal communication in my teaching of Middle Eastern “bellydance”. The Modern Dance piece will show an example of how dance can is being used alongside education in schools to help children make sense of the everyday problems they have growing up with their peers. The dance is performed by Weisser Park Elementary School Dance Troupe in Ft. Wayne, Indiana, and the song is “Breakable” by Ingrid Michaelson; choreography by Brittney Coughlin.

Analysis:

Three Examples of Communication Theory of Dance as Non-Verbal Communication:

- Applied Dance Method by Dr. Hanna:

“Youngsters learn in different ways, and dance requires multiple intelligences” (p499)

As a California state-certified social studies and English high school teacher and dance educator, Dr. Hanna offered a dance-centered course at Gill/St. Bernard’s High School, in Bernardsville, New Jersey, in 1972, and she witnessed students learning the language of dance as an entry point into academic studies (p499). By using the dances as the launching pad into the culture, she had her students research the histories of the people and cultures they were dancing. They also had to write critiques of dances they had seen at the Lincoln Center in New York City, and then compare them with critiques from the New York Times the next day (p499).

Her experience proved that the students found other educational opportunities that branched off of their dance knowledge. As dance uses the same functions in the brain as being multilingual, it opened up the tangent career possibilities for those who do not want to become professional dancers. Students became more motivated to go into dance-related careers, such as dance program fundraiser, promoter, writer, administrator, photographer, or therapist, all of this made possible by an appreciation for the arts through studying dance.

The transfer of learning from dance over to other fields is apparent when students, for example, can solve math problems by referring back to their knowledge of rhythm learned while dancing. In literature, a student may use references to encode meaning into a dance. She ascertains that most methods of measuring the transfer of learning have been inadequate.

“Preparation for future learning, including letting go of previous approaches, resisting easy interpretations, and asking sophisticated questions, leads to learning activities that are most likely to help people acquire expertise in a field. Such activities are the staples of creative dance classes.” (p 500)

- How I Have Interpreted Her Research: My New Teaching Method-

The reason I have come to this program is out of frustration with how Middle Eastern dance is taught in this country, and particularly at the university level. My aim is to begin to codify our dance and make it easier to teach, so that students learn more quickly, and is based on a cultural/musical format. In this section I will discuss my emerging theories on how communication theory as purported by Dr. Hanna can be applied to teaching bellydance.

One of the main problems in teaching dance is that cultural and musical concepts are not always included. Looking at the history of dance in academia we can see where the divide occurred; as dance started in physical education departments the emphasis was on the movements, and not necessarily on the cultural affection and musicality one needs to be able to fully comprehend a dance. For example, ballet is the only dance that has been included in the Indiana University School of Music, as it closely follows classical Western European music. However, musical concepts are not taught in class, except in the form of learning the beat in the form of 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8, and learning the names of rhythms; with melody they must learn what the meaning of the song is, and maybe some history, but they are not required to understand the notes the way a musician does.

This kind of teaching is what prevails in most traditional classrooms and ballet classes across America; that is, primarily teaching to the left side of the brain, which is the logical and linear thinking side, and not the creative and nonverbal side. Looking back at Dr. Hanna’s research, we can see that both sides need to be employed in learning for there to be full comprehension going on, and especially the transfer of information across the corpus collosum, which forces the brain to use both sides at the same time to solve a problem. For example, according to Dr. Hanna “there are left-hemisphere processes for words spoken or spelled out and right-hemisphere patterns for representations of numbers (visual Arabic codes) that have interconnectivity by direct transcallosal pathways” (p494).

Arabic Language Concept for Teaching Dance: Root/Pattern-

My new teaching method for Middle Eastern dance is based on Arabic language concepts, which follows the right/left brain responsibilities. “Arabic is an ocean” is a saying about the Arabic language, meaning that it is vast. All words in Arabic have a root and a pattern, “jathdar and wauzen”, that they fit into; all words can be traced back to these basic concepts. For instance, the word “jameel”, which means beauty, has the consonant root of j-m-l, and the vowel pattern of “a-ee”. The root of the word uses the functions of the brain on the left side, that of linear information processing and analytic functions. The pattern of the word uses the functions of conceptualization, creativity, and spatial information. Understanding how a people conceptualize their verbal communication will give clues as to how they conceptualize their non-verbal communication. Arabic dance is like Arabic language in that all movements have roots and patterns that they fit into, and all movements can be traced back to a root and a base pattern. Arabic dance is also an ocean.

Teaching the root patterns is fairly straight-forward, as it is dependent on static principles, but putting these roots into patterns takes a creative teaching approach, and is not always easy. My teacher and mentor, Leila Gamal, is brilliant at teaching concepts, and she has a class called, “Choreography Soup” in which she teaches these ideas. Her class follows the concepts of:

- Theme and Variation

- Lines: horizontal, vertival, spiral, implied line, delayed line

- Floor Design

- Parts of stage: center, diagonal, right, left, back; quality of design, passive/aggressive; figure-8 design

- Spaces

- Floor; space; air

- Layers

- On the body, lower, middle, upper; Indian chakras concept.

- Weight Change

- Use floor with feet; use spine position;

- 1 weight change over 4 beats; standing still

- 2-weight changes over 4 beats; accent on one beat

- 3-weight changes over 4 beats; holding one beat, any beat

- 4-weight changes over 4 beats: turns, changing each beat

- Turns

- body lines

- Tempo

- Crescendo or decrescendo;

- Slow/fast

- Count half-time or double-time

- Timbre

- Staccato, legato or tremolo

- Sharp or soft

Another concept that I have noticed of the root/pattern concept in verbal language, is that it is similar to the Arabic music concept. The root is the consonants of the word, and the pattern is the vowels; the root is the melody of a piece, in that each note would be static if it did not have the rhythm to move it to the next note. The pattern is the rhythm that provides that movement to create a complete musical phrase. It takes both sides of the brain to make music.

Gender-Specific Teaching Methods

It is my experience in Middle Eastern dance that women and men teach very differently. This is by no means an algorithm for gender-specific teaching, however it does follow the archetypes of gender, which can be embodied by either male or females. There are many more female than male teachers, and this must be acknowledged, as it is a women’s dance.

For a man to teach, he is usually an experienced native dancer, steeped in years of dance training, including Western as well as folkloric dance, and he must be a well-known performer. My coach and mentor, Mohamed Shahin, is a good example. He is Egyptian, and studied with Mahmoud Reda, the leading folkloric dancer in Egypt. The male approach to teaching dance caters to the left side of the brain’s learning style, the side that caters to memory of analytic functions. Also, following in the ballet tradition, many male teachers do not nurture their students in the classroom; there is seriousness to the teaching style, a kind of military precision to the class. Choreography is often the preferred method of teaching for men, and is the way of Western dance.

Women are the opposite of this; they teach to the right side of the brain, the creative, inspirational, and musical side. Concepts of dance-making are employed, and improvisational skills are acquired through understanding concepts of spatial information, musicality, affectation, and emotional reactivity. A good example of this teaching style is Dina, the Queen of Cairo Bellydance. When I took her workshop in Miami in 2005, many student became frustrated when she would not break down a dance pattern into “1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8”, as they wanted a logical, rhythmic pattern to hear the music, and she was forcing them to dance to the melody, which slides over beat to beat. She stopped the class and said, “Ok, now that we are behind closed doors, I can tell you the truth: There IS NO 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8…It is all ONE!!!” She was asking us to hear the piece of music, and hence see the movements, as all interconnected, that there was no stop between beats. She was not teaching in a Western dance methodology, but was teaching in an Arabic music methodology, asking us to hear the music as Arabs do, not as Westerners do.

Another key concept of Arabic language that can help us to see what Dina was talking about is the math concept of Algebra; all numbers must be reduced to their common denominators and added or subtracted down to one number. In Arabic language, one must conjugate the sentence one section at a time, because each word is influenced by the other words around it.

What I have done is take one significant movement to bellydance, the “shimmy”, and just reorganized my thought patterns about it. I arranged it according to seven different concepts about the shimmy: the first five are language specific, and the last two are music specific.

Below I the class format; I gave this to my students as a handout:

The Art of Shimmies: 7 Different Shimmies Workshop at the Indiana Dance Festival, 4-2-11

“Where Western dance explodes at the climax of the music, Oriental Dance implodes”

~Maleha, Oriental Dancer

*Shimmies, along with jumping rope and jumping on the trampoline, are the only activities that are vigorous enough to get our sluggish lymphatic system moving. Let’s get shaking and implode!!! J

Warm-Up: Stretching; music-“Rivers Winding” & “Sea Tea” by Joe Zeytoonian

- Sun Salutation x3 or 4

- Stretching on the floor; straddles and splits

- Martha Graham 4th position on the floor

Warm-Up: Basic Isolations (basic stance; basic positions); music-“Maarwa”, Egyptian pop song

- Snake arms; basic hands

- Undulations

- Figure-8’s; Around the World; Pelvic circles

- Chest isolations; chest drop/lift

- Hip drop/lift

- Egyptian Series Shimmies: music-“Tabla & Doff Solo” (Saidi rhythm)

- Basic Egyptian Shimmy: Comes from knees; release hips to absorb vibration; body upright in basic stance. Hip locks come from this movement.

- Egyptian Vibration: Small version of basic; body has the appearance of “vibrating”

- Egpytian Shoulder Shimmy: Small shoulder shimmy; movement originates in the shoulders, but shows up in the chest.

- ¾ Shimmy-(will be covered later as it is a travelling shimmy)

- Shimmy Layering: Add the basic isolations

- Lebanese shimmy: Same as Basic Egyptian, but larger.

- Turkish Shimmy Series: music-“Asena Baladi”

- Basic Turkish Hip Shimmy: Twisting of hips horizontally; slight leaning back of upper body.

- Turkish chest drop/lift-solar plexus shimmy: Movement comes from the diaphragm; extension and contraction of the muscle in short staccato repetitions.

- Turkish shoulder shimmy: Fast, repetitive staccato movements; comes from folkdance.

- American Shimmy Series: music-“Solo Drums” by Amir Sofi

- American Hip Shimmy: Comes from Turkish hip shimmy; concentrated on the derriere.

- Flutter: Diaphragm isolation and quiver.

- California Earthquake: Movement originates in the feet and knees; vibration moves up from the ground to the hips; body must stay relaxed to absorb the vibration, and show the movement in the chest.

- African Shimmy: music-“Drum Solo” by Harem

- Movement originates in the feet; repetitive stepping in place back and forth, and pushing the movement into the hips; hips should stay released to absorb the vibration.

- Choo-choo pattern

- Turns; in place; travelling.

- Travelling Shimmy-3/4 Shimmy: music-various Egyptian pop

- Half-time: In Place: up-down-down-up pattern.

- Full-time: Across the Floor: “1-2-3”-3/4 Waltz feeling in a 4/4 beat.

- Folkloric: flat-footed with arms in Folkloric 2nd position ( bent up at the elbow).

- Oriental: on releve` with arms in Oriental 2nd

- Related movements:

- Hip-Swing Back-Shift

- Hip-Lift Forward Walk

- Musical Interpretation: Rhythm “Al Tabla Al Majnouna” (The Crazy Drum)

- Drum solo

- learn rhythm names, country of origin, time signature, etc.

- repeat in patterns of 4 (8, 16, 32, etc.)

- Musical Interpretation: Melody, music-“Shahat Al Gharam” (The Beggar of Love)

- Raqs Sharqi Composition:

- Rhythmic interpretation of the melody

- Musicality: Hossam Ramzy’s Formula of Dance, E=E: The dancer makes the musical sound 3D.

- “Been There Done That” Dance Article:

- Raqs Sharqi Composition:

- Drum solo

http://www.hossamramzy.com/dance/dance_been1.htm

- Affectation: emotional interpretation of the music

Cool Down: music-Classical taqsim, “Kanoon Mood”:

- Instruments for the Shimmy:

- Oud: staccato or tremolo notes

- Kanoon: anytime

- In place shimmies only for taqsims!

- For travelling, switch to burre foot pattern.

- Drink lots of water after class to flush your body of toxins that your lymphatic systems has moved for you! J

My experience at the Indiana Dance Festival-

The students that I taught were mainly intermediate level, but I did have a few beginners, and also a few who were brand new to the dance. The idea of the class was to give them basic movements and basic concepts that they can put into patterns immediately. Bellydance is all about the isolation, and also all about layering movements; so we spent a lot of time improvising within certain parameters that I gave them. The students feel like they are dancing right from the start, and that emotional interpretation helps them to use both sides of the brain at the same time, and also gives them confidence to learn more. The 7 Shimmy Concepts are according to cultural dance genres and themes: The Egyptian Series, The Turkish Series, The African Series, The American Series, the Travelling Series, Rhythmic Interpretation, and Melodic Interpretation.

“Oh, Ethnomusicology, that’s a good place for you, isn’t it?”

This was said to me by a Modern Dance academic professor who was asking about my dance research. Clearly, she would not have known what to do with me if I were in a Modern Dance program and wanted to bellydance; she did not know what Ethnomusicology was, and thought it must be a good place for me to be, since it was not ballet, and certainly was not Modern Dance. These are sentiments and values that are communicated in Modern Dance, as it follows a primarily Western European white aesthetic, and although borrows “ethnic” movements, makes no reference to the cultural or musical heritage of the movements.

We are communicating much more than just what we intend with the dance; other values are communicated that may or may not be the intention of the dancer/director/choreographer. For instance, I overheard a high school ballet dancer say when asked about the effectiveness of a nutritionist coming in to help the ballerinas with their diets, “What are they (the directors) communicating to us when they only pick the anorexic girls for the best roles? No nutritionist will solve this company’s eating disorders until they stop that.”

- Communication Theory as Applied Dance for Elementary School Children-

Lastly, I would like to share with you a dance piece performed by Weisser Park Elementary School Dance Troupe in Ft. Wayne, Indiana. This was performed at the Indiana Dance Festival, sponsored by the Ft. Wayne Dance Collective on April 2, 2011. The song is “Breakable” by Ingrid Michaelson, choreography by Brittney Coughlin. Here are the lyrics, and I think you will see when you watch the dance, that the non-verbal communication story told through the dance enhances the lyrics, and makes it a full picture:

“Breakable” by Ingrid Michaelson

Have you ever thought about what protects our hearts?

Just a cage of rib bones and other various parts.

So it’s fairly simple to cut right through the mess,

And to stop the muscle that makes us confess.

And we are so fragile,

And our cracking bones make noise,

And we are just,

Breakable, breakable, breakable girls and boys.

You fasten my seatbelt because it is the law.

In your two ton death trap I finally saw.

A piece of love in your face that bathed me in regret.

Then you drove me to places I’ll never forget.

And we are so fragile,

And our cracking bones make noise,

And we are just,

Breakable, breakable, breakable girls and boys.

And we are so fragile,

And our cracking bones make noise,

And we are just,

Breakable, breakable, breakable girls-

Breakable, breakable, breakable girls-

Breakable, breakable, breakable girls and boys.

Find More lyrics at www.sweetslyrics.com

Conclusion:

According to Dr. Judith Hanna, dance as non-verbal communication “has been shown to help explain how dance educators use dance to communicate concepts of aesthetics, agency, release of the imagination, lived experience, the power of the arts to engender visions of alternative possibilities, transcendence, and learning through the body (p 501). In today’s world of very little learning happening in the classroom, because of stress factors of children beyond the scope of the teacher, kinesthetic learning could be the key to unlocking the doors of so many young minds who cannot learn in a traditional classroom setting. It can also be a concept that is applied to dance itself, to help students bridge the gap between dance as physical education and dance as a serious profession. Modern Dance has the best application of applied dance learning, however, other dance forms can benefit, as Modern does not necessarily focus on cultural or musical traditions.

Sources Cited

- Communication Theory, (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communication_theory, 4-21-11)

- Dina (famous Egyptian bellydancer), private communication, 2005.

- Gamal, Leila. Private communication, March 17, 2011.

- Hanna, Judith. To Dance Is Human: A Theory of Nonverbal Communication. Revised 1979 edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1987.

- Hanna, Judith. “A Nonverbal Language for Imagining and Learning: Dance Education in K-12 Curriculum”. Educational Researcher, Vol. 37, No. 8, pp. 491–506.

- Shahin, Mohamed. Private communication, April 2006-present.

- Stone, Ruth. “Theory for Ethnomusicology”. Pearson Prentice Hall Publishing. New Jersey. 2008.