Introduction

The subject of discrimination towards Asians and Arabs in the media as defined by Dr. Edward Said’s groundbreaking book “Orientalism” in 1978 and American bellydancing has been discussed at length since 911 happened in America. The issues of Arabs getting portrayed negatively in the media has increased dramatically since this tragic event, and at the same time, bellydancing in America hit an all-time high in the 2000-10’s. What happened? Are the two phenomenon linked, and if so, why? Is this just a case of cultural appropriation, or is there more to the story? As a dance scholar, ethnomusicologist, music producer, and professional bellydancer in the Detroit and Indianapolis areas I can attest to the fact that Arab music and dance is alive and well and thriving in America, and has been for about sixty years. The Turkish, Armenian and Greek immigrants of the 1950’s-60’s in America has shaped the landscape of American bellydancing, and is the foundation upon which all of the other sub-genres developed in the US. It has been difficult to dance since 911, but bellydancing is still happening. My experience is that after 911 dancers felt a need to stand up for their Middle Eastern friends, and so the dancing increased as a show of support, not a vehicle for mockery. There are some misunderstandings about this, so let’s take a look at what they are. I believe that the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and its impact on the lives of the immigrants who came here created the mindset from which the US bellydance culture sprang; it is not US Imperialism and White Privilege that made bellydance so popular in America. The Democratic Republic of Turkey as formed by Ataturk, which split church and state, and the reformation of the Turkish language created an atmosphere of change and freedom; this is the premise to American bellydancing.

Since Ataturk’s revolution and its impact on the women of Turkey created the “bra burning” feminism phenomenon of the 60’s bellydance scene, let’s take a look at what Ataturk did to the language, religion and cultures of Turkey, and its impact on modernity.

The place of religion in the construction of the Republic of Turkey

During the Ottoman Empire Islam ruled the government; religion and politics had no separation. The inequalities between classes, education, and gender posed threats to the balance of the state. The Ottoman state had to take care of not only its Muslim, but also its Christian, Jewish, and pagan believers under Islamic rule; that hardly was a fair system for non-Muslims. Eventually, the collapse of the old empire happened, and out of the ashes of it came hope for a future. As religion posed as the main problem for the Ottomans in ruling such a vast dominion, the separation of religion and state was imminent, and made way for the birth of secularism in Turkey.

So what place does religion have in the new construction of the Republic of Turkey? Actually, there is no official place; religion is now seen as a personal choice, not a matter of official state protocol. I find it interesting that soldiers in the Turkish Army are not allowed to have any religion whatsoever; if they do have one, they are not allowed to practice it. This is done to curb any kind of religious fanatics who seek to use political and military force in the name of God. Religion is not taught in the school systems as it was during Ottoman times; a more European guideline is used for classroom instruction in modern Turkey. Obviously, there are many benefits to separating religion and state; a secular government represents more peoples, and the bias that was once seen towards Muslims is now gone.

There are a few cultural artifacts of Turkey that got swept under the carpet of the reformation; one of them is the Sufi Tekkes. These are the local houses where the Sufi Sheikhs and their respective orders would hold their semas, or musical prayers. From what I understand, there were the elite Mevlevis, who mainly had more wealthy patrons, and then there were the more poor Bektashis of the rural areas. Perhaps the downfall of the Tekkes was the class distinction; it seems to me that after a time these societies functioned more or less like fraternities of influence, rather than proper religious affiliations. They are definitely cultural artifacts, so during the reformation the Tekkes were kept alive for purely tourist moneymaking purposes. One can now visit a Tekke in Turkey and watch perhaps a Mevlevi whirling ceremony along with other tourists; during the Ottoman days that would be unheard of, as they functioned as secret societies with a sort of membership. While the word “brotherhood” is definitely used to describe the Sufi orders of today, it is a much more open environment in Turkey; in other areas of the Islamic world just the opposite is true, there is a growing fundamentalism that is spreading amongst the Arabic tariqas.

While the religion of Islam had a central role in the government of the Ottomans, it became the main component that was extracted in the government of the Republic of Turkey. Religion was seen during the reformation as the main problem for Turkey; keeping it in a personal space was the solution, and out of the reins of government. Some in Turkey would say that it was a mistake, but I believe an overwhelming majority are happy that this transformation took place. Making Turkey a secular state put it in the candidacy for becoming a major world leader, and on the road to improving the lifestyles of the Modern Turkish people.

The importance of the “Age of Tulips” for the development of Turkish secularism

The “Age of Tulips”, as coined by 21st century scholars, was a foreshadowing to the reformation into the Republic of Turkey. It took place roughly between 1703-1730, and was named for the influx of European goods and culture; tulips, or “lale” in Turkish, were a symbol of Western culture infiltrating the country on the border between East and West. Even though after 1730 the country was less interested and influenced by the extravagance of Europe, this “Age of Tulips” was a sparkler compared to the fireworks explosion that occurred during Ataturk’s reign.

Perhaps because of the extravagances of the Ottomans there was an interest in the culture of the Europeans; it seems to me that people during the early 18th century were starting to get more of a world view, and the people in power were looking to advance their kingdom; it was called a “flexible world”. Yirmisekiz Celebi Mehmed Efendi was sent on a mission to Paris in 1721 to investigate French civilization and science; when he came back much of what he learned was incorporated into the Ottoman elitist culture of the court. The notion of “Westernization” has roots in the “Age of Tulips” with one exception, that of military reforms. A change in outlook of the Turkish military infrastructure did not occur until the 1730’s, technically after the Tulip Age.

A rational and liberal attitude prevailed during this time; for example, it can be seen in the world of medicine, and education. Sultan Ahmet III went through several regulation changes with the advent of the new Western medicine. Standard examinations and a diploma were put into place to make sure doctors were qualified to practice Western medicine. This was a progressive time; the educational system felt the winds of change, too.

The political, cultural and linguistic significance of the Turkish alphabet and the language revolution

The formation of the Republic of Turkey can be seen through many lenses, one of which is the lens of the language revolutions; finding the true Modern Turkic alphabet and common language was the aim of this part of the reformation. Why did they feel this was necessary? Just as religion was taken out of the government to form a secular state, so all “foreign” elements were extracted out of the spoken Turkic language. These foreign elements are words and phrases borrowed from other languages of influence in Turkey, such as Arabic, French, Farsi, etc. The need for this arose out of a new nationalistic spirit created by Ataturk; along with the formation of a new government came a new Turkish identity, and a need to communicate differently to establish Turkey’s new personality in the world.

As there are many branches of the Turkic language tree, and many regional dialects within them, one can imagine that overhauling the entire official language of Turkey was quite a task. Also, teaching the new language in schools presented challenging, as new education guidelines were also a part of the reformation in Turkey; the literacy rate before Ataturk was quite low, but now everyone was encouraged to learn to read and write. I can imagine that in switching gears between the two forms of the language there were some kinks to work out in the beginning. Some of the problems may have been perhaps because of the regional dialects people would learn to write the new language, but not speak it; or, the opposite, that the regional dialects would lose their cultural and historical “color”, and become like dinosaurs. Ataturk made it illegal for any other language than the new Turkish to be spoken, so people who spoke languages such as Armenian and Kurdish became enraged, which has created conflict between the cultures.

How did Turkish become so enmeshed with words from other languages? One must consider the cultural history of Anatolia; even before the Turko-Mongol tribes swept down from the Russian steppes, there were many different peoples already living in Anatolia. The languages of the Kurds, Armenians, and Persians certainly must’ve influenced the invading conquerors’ speech. After the conquests one must look at the relations with the peoples surrounding Turkey, namely the Arabs, who not only brought their language to Turkey, but also their religion. Another neighbor that has influenced Turkish language is Greece; it is the closest neighbor, and shares much in linguistic ties with Turkey. One can see that culture is not limited by any religious or political problems, regardless of any tensions between any of the above-mentioned groups of people. If people are living on the same land, it is inevitable that they will share lifestyle and culture, and language is a large part of culture.

There are also farther reaching languages that affected the Turkish language, particularly the Ottoman dialect. French was very fashionable during the Ottoman Empire’s rule, and many words were incorporated into the language, just as they were in Farsi. I believe it was a status symbol to be able to use as much French as possible, and I’m sure only the elite had access to the education to give them the knowledge to distinguish themselves amongst their peers and society. Also, the Ottoman palace schools must’ve been the place where this knowledge was circulated, as the madreses were primarily for religious, math and science education. If Ottoman was infiltrated with French, then that explains why the court poetry uses it, as well, which would make it even more of a status symbol.

The Significance of Ataturk on American Bellydancing

In an article by Sunaina Maira, “Belly Dancing: Arab-Face, Orientalist Feminism, and U.S. Empire”, she states that American imperialism and colonialism are to blame for this rise in popularity of bellydancing, and that white women are the culprits for this bastardization of Arab culture. In reality it is the Arab leaders who sold their people and countries to the US, and if anyone is to blame for the demise of the Middle East it is them. The author is actually talking about American Tribal Style Bellydance (ATS), but doesn’t seem to see the difference between traditional raqs sharqi and ATS, and I find this problematic. This was my first red flag that the premise of her whole argument was wrong; if the epistemological foundation of an argument is based on misinformation, then the entire point she is making is off. Maira herself is not Arab, she is South Asian, yet she feels confident to speak for them as she is a Muslim. Second red flag. I find her viewpoint to be ethnocentric; she is speaking as an Asian woman about a non-Asian phenomenon. Not all Arabs are Muslims, so I feel that her viewpoint must be religiously motivated. It’s very convenient for authors such as her not to state that many Arabs are Christians; Jesus was a Palestinian Jew after all. I can attest to the fact that after 911 racism towards both Muslim and Christian Arabs increased, and that people were afraid to use the word Arab when referencing bellydance, but the reason the word “Middle Eastern” is used in reference to bellydance is because it’s not all Arab, it’s Turkish, too. Turks and Persians are not Arabs, so using the blanket term Middle Eastern covers all territories.

I found Maira’s theoretical approach and methodology not to be thorough, and she is spreading her viewpoint and not facts, which is misleading and dangerous. Third red flag. She is starting with an hypothesis and then working backwards to try to prove it. She bases her research mainly in San Francisco, and ignores the largest Arab American community in North America, Detroit. Also, the research methodology in the social sciences is not like the hard sciences in which an hypothesis that you are trying to prove is the starting point of the research; rather, it is the end point, and sometimes you may not even get any real point you’re trying to make. Sometimes ethnography is just verbal photography; you are capturing a culture at a time and place and documenting it. Participant observation is the foundation of good ethnographic research, and I didn’t see that Maira even tried to take a dance class. What she did is the worst kind of research you can do in any kind of cultural anthropology writing, whether it’s an article or an ethnography. I’m not sure what her field is, but it is clear she is versed in historical analysis, and uses her writing skills to shame and bully women into not dancing. Good research should be emergent, meaning theories should emerge from the work in the field; and, good research should be indexical, meaning you can index or refer back to historical occurrences and references on your subject. Good research should be based on discourse, and as I know the American bellydancing community well, Maira’s statement that American bellydancers are not as interested in learning Arab culture is not based on fact, she did not interview enough people to come to a quantifiable conclusion. She did not interview enough people to be able to say that with confidence, and again, she is coming from a religious viewpoint and she is not Arab, or Turkish. She does attempt to reconstruct the history of American bellydance, but she is not thorough or accurate; perhaps 65% of what she wrote was based on fact. This author has an axe to grind, and I do applaud her for standing up for what she sees as “the truth”, which is that Arab Americans are being persecuted after 911; I actually agree with her! But she is blaming bellydance and bellydancers as being complicit in this racism, and I do not agree. She has missed some major historical happenings in America to have a well-rounded enough opinion on the placement of feminism and bellydance in the US.

I have been bellydancing in America since before Maira was born, and I can tell you, she has missed a gigantic historical factor that would shift her whole premise if she knew it. It is clear that Maira is reflecting upon the genre of American Tribal Style Bellydance (ATS), and not traditional raqs sharqi, and she lacks discernment. I’m not sure if she was aware that 90% of what she was talking about was about ATS, and not traditional raqs sharqi, which is what “bellydance” is in Arabic, and which is enjoyed by most Arab women. She is based in San Franscico after all, and that is the home of ATS. She is also doing what many, and in fact, almost every Arab has done that I’ve spoken to about bellydance and orientalism: they only speak about Arabs, and forget that Turks also bellydance. In fact, bellydance is actually Turkish, not Arabic. If you ask Turkish people where bellydance came from they’ll tell you it’s Arabic, because of Egyptian dance. If you ask Arabs where bellydance is from they will say Egypt, but they will say but it’s really Turkish because the Ottomans brought us the music we dance to today. Actually, they’re both wrong, I would say the roots of raqs sharqi start where classical Arab music was formed: the royal courts of Baghdad. Yes, raqs sharqi compositions are based on classical Arab music, which is Syrian music made Egyptian, but before that it came from Baghdad, Iraq. Before that it came from Iran, as Baghdad was a part of the Persian Empire before Iraq. The dance we have today came from the Ottomans who came to Egypt and Lebanon in 1516 A.D. and merged with the dancing they found there.

Maira also glosses over the fact that the reason white women bellydance professionally for money in America is because it is frowned upon for Arab women to dance by their families. There are some Arab women that perform, of course, and they always make more money than the non-Arab dancers. You see, this is what researchers such as Maira miss who are not in the dance genre, and do not do proper research to get the correct answers: there is a glass ceiling that non-Arab dancers hit as far as pay scale. It may seem from the outside that it is unfair for non-Arab women to make money off of an Arab dance, but foreigners will never get paid the same by Middle Eastern clients as Arab dancers.

So, is bellydance Arab or Turkish? That depends on who you ask, but I believe the Turkish immigrants who came to this country influenced us the most today. Yes, Little Egypt and the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago had an impact, but raqs sharqi dancers are not performing that way today. The way we dance today is based on the clubs of the 20th century America that had live music in the urban areas, such as Chicago, Detroit, NYC, LA, and Boston. Clubs such as the famous Fez Nightclub in LA was a home away from home for many immigrants, so naturally sharing and mixing of music and dance styles occurred and created the American Cabaret style bellydance we have today. This is NOT American Tribal Bellydance.

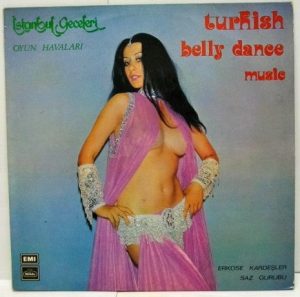

The fact is that the dance is non-verbal language, and is covered under the US 1st Amendment of Free Speech; you can’t tell anyone what to say in America, and you can’t tell anyone how to move, either. Turkey under Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s rule created a whole new language, he made speaking Armenian and Kurkish illegal, he made the government a secular democracy, and he “liberated” women from the rule of a religious government telling them what to wear. One only has to look at the Turkish bellydance album covers of the 1960’s to see that the women were wearing pasties instead of bras and know that the “bra burning” feminism of that era was not secluded to America. The Turkish immigrants from Ataturk’s era who came to this country brought this liberal feeling to bellydance, it did not originate solely in America. Actually, white America was founded by Puritans from England, and they were against anything as scandalous as what Little Egypt had to offer. This Puritan viewpoint is really at the core of the American Tribal Bellydance movement; they see feministic empowerment as de-sexualizing the dance.

Traditional raqs sharqi as performed in the US was brought here by immigrants mainly from Armenia, Turkey, Greece, some from Syria, and some from Lebanon in the 1950-60’s; very few Arabs at this time were playing in the genre. The style known as “American Cabaret” bellydance is based on Turkish bellydancing of this era; it is not based on Egyptian, or even Arab, dancing at all. Egyptian dance became popular in the US in the 1980’s; up until then it was Turkish. The musicians and dancers at the clubs in Detroit, Chicago, Boston, New York, and LA taught American women in their communities about bellydancing, and today we have a thriving community and industry. Contrary to what Maira reported, many Arabs, Turks, and Persians hire American bellydancers for their family parties. In fact, I am known as the “family dancer” in Detroit, because this is what I love to do: Arab weddings, baptisms, first communions, etc. I love to be with the Arab families, and the ones who hire me are OK with me being non-Arab, and they get a kick out of the fact that I love their culture so much. This is what the author is missing.

American Tribal Style Bellydance didn’t come along as a valid genre until 1996; I actually remember when this happened, and dabbled in it a bit, but it never sat right with me to reinvent someone else’s culture, so I went back to traditional raqs sharqi. Some Arabs will tell you that “bellydance”, raqs sharqi, isn’t Arabic at all, that it’s an invention of the West. I say you have to be a blind fool to think that, all you have to do is go to an Egyptian or Lebanese club and see that bellydance is definitely something that Arab women love to do, and they will laugh in your face if you tell them it’s something that the West created; only religious zealots think that. I’m afraid Maira is falling into this category. The West has definitely changed bellydance, but it is not just white American women who are to blame. Actually, I have found that the worst offenders of orientalism are people from the culture of origin themselves who purposefully mislead foreigners about their culture just to make money. I guess the thinking is, “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em”. Some of the best and most well-intentioned teachers of raqs sharqi are foreigners who care so much about the dance that they go above and beyond their native counterparts to make up for this lack of cultural background.

Turkish Bellydance Album Covers from the 1960’s

Conclusion

The process of the development of the Republic of Turkey with an objective and historical perspective now looks like a purging process; in order for there to be a rebirth of a new country and government, the old had to be extracted to make way for the new. The language reformation was a great symbol of this birthing process that Ataturk began; it stirred up national pride in the country’s founding and history, and unified all the peoples living in Turkey under one official language. It also made the minorities persecuted for speaking their own languages, and caused discord while he was trying to create unity. I’m not sure that Ataturk achieved his aims of a unified Turkey, but one thing’s for sure: Turkey will never be the same because of him. The influence that this had on the immigrants that brought us Turkish music and bellydancing in the 1950-60’s was enormous. This generation saw their parents’ culture completely overhauled, the Ottomans were gone; WWI and II had happened, and it shifted their perspective about traditions. You can blame the US on the evolution of raqs sharqi, but I believe Ataturk and the Turkish language revolution had a vast impact on the bellydancing origins in America through the immigrants who came here.

Sources Cited

Maira, Sunaina. “Belly Dancing: Arab-Face, Orientalist Feminism, and U.S. Empire”. American Quarterly. Johns Hopkins University Press. Volume 60, Number 2, June 2008, pp. 317-345.

Silay, Kemal. Indiana University, Bloomington. Class notes, Literature of the Ottoman Court. 2001.